Techniques of Escape: John Wyndham's Chocky

Techniques of Escape: John Wyndham's Chocky

Archeology of the Future has been raiding the mouldering piles of paperbacks in the cupboard under the stairs, digging through the accumulated strata to uncover some rich gems.

Chocky by John Wyndham, published in 1968, is the story of a family afflicted, or blessed, with a 'special child'. Rather than dealing with a wider apocalypse or with the world plunged in violent change, Chocky is the exclusive story of one suburban English family. It's a novel of relationships; the relationship between husband and wife, between father and son and between a young boy and an intangible presence that takes up residency in his mind. There is a great change, but not necessarily the one that the reader might expect.

Before we discuss Chocky and the boy who brings him/her to our attention, we’d like to introduce you to another outlandish figure, an almost- contemporary of Chocky:

“Alan Measles was the leader, the benign dictator, of my made-up land, the glamorous, raffish, effortlessly handsome, commanding character… When I was about ten, I worked out the game was set one hundred years in the future in the 2060s and 2070s. There had been a calamitous nuclear war, almost obliterating Planet Earth. Everyone agreed that technology had advanced too far, so an international agreement was forged stating that from now on technology could only move backwards. Armies once again began to use old-fashioned, conventional weapons.”

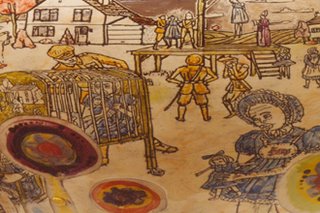

In the book ‘Grayson Perry: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl’, a book of interviews with the 2003 Turner Prize winning artist by Wendy Jones, Perry outlines the content of his childhood fantasy world ruled over as it was by Alan Measles, his teddy bear. A series of rationalisations that allowed him to include whatever toys, and later Lego and Airfix models that came along, the world of Alan Measles, improvised from the topography of Perry’s bedroom, provided both a rich territory for the young Perry’s imagination but also a refuge from his disrupted home life and uneasy, and often violent, relationship with his stepfather. As Perry says:

“Alan Measles was the ultimate male presence. The Germans were the invading force, or at least they were as soon as my stepfather appeared on the scene. Gradually, the Germans occupied Alan Measles’s realm. As the years passed, Alan became more of an underground guerrilla, more a spy. In the beginning it had been open warfare, whereas towards the end it was subterfuge… As I was growing up I progressively bestowed all my noble masculine traits of a high achiever, a winner, a lover even, on to my teddy bear for safe keeping. He was the guardian, the custodian of these qualities. “I lived in Alan Measles’s realm, carrying it around with me like a comfy sleeping bag I could pop into at any time… I no longer had separate games, they were all facets of the one game: everything was linked..”

“Alan Measles was the ultimate male presence. The Germans were the invading force, or at least they were as soon as my stepfather appeared on the scene. Gradually, the Germans occupied Alan Measles’s realm. As the years passed, Alan became more of an underground guerrilla, more a spy. In the beginning it had been open warfare, whereas towards the end it was subterfuge… As I was growing up I progressively bestowed all my noble masculine traits of a high achiever, a winner, a lover even, on to my teddy bear for safe keeping. He was the guardian, the custodian of these qualities. “I lived in Alan Measles’s realm, carrying it around with me like a comfy sleeping bag I could pop into at any time… I no longer had separate games, they were all facets of the one game: everything was linked..”This retreat into fantasy as defence and the creation of an avatar representing some essential qualities was a key experience for Perry, as they represent a kind of reflexive therapy and playing out of drama that would eventually find expression in his art. For those unfamiliar with his work, Perry works in ceramics, producing glazed vases and other objects with images and photographs that, to us at least, are reminiscent of Pulp songs, with an uneasy mixture of fantasy and ‘kitchen sink’ reality.

In many ways, the realm of Alan Measles seems to have prompted Perry into pursuing certain paths, as if such interior richness, once tasted needs to be returned to repeatedly in different ways.

In Chocky too, there is a figure that exists in the mind of a small boy, but of a small boy with a very different set of problems.

Matthew is the adopted child of the stable Gore family of Hindmere, Surrey, happily undertaking the pursuit of a normal English childhood. His father, David, the narrator of the book, tinkering with a lawnmower in the shed, overhears Matthew one sun kissed suburban afternoon arguing with an unseen 'friend’ about the number days in the week and the number of months in the year. Before he can see who it is that Matthew is arguing with, a child from next door calls and Matthew runs off to meet him.

For David Gore, the narrator and patriarch of the Gore family, this is the beginning of the story of Matthew and his involvement with Chocky.

David and his wife Mary debate the best course of action, reasoning that Matthew may be too old for an imaginary friend, but also intrigued by the ‘unMatthewness’ of the questions that he has taken to asking. Hoping that it is a phase that Matthew is going through, like his younger sister had with her imaginary friend Piff, they agree to keep a benign eye on things.

As the novel progresses, Matthew causes consternation at school with his outlandish questions about matter, space and intelligence. He becomes extremely upset when the family buys a new car, only to have Chocky criticise it as primitive. In art class at school, he finds that Chocky can show him how to do things if he lets his mind go blank, channelling Chocky’s will through him, producing drawings, that while technically proficient, present a certain off kilter air. He manages to save his sister from drowning when they are both deposited into a river when a boat hits a jetty, despite previously being unable to swim. When asked how he did it, he can only answer that Chocky showed him. After coming to national prominence as a boy who was saved from drowning by a guardian angel, as well as winning a prize for his drawings completed under the influence of Chocky, Matthew is finally abducted by the government, which prompts the departure of Chocky.

Despite being a story about a possible alien incursion into the life of a young boy, Wyndham gives the reader no solid confirmation that Chocky is an actual real entity, despite both David and Matthew believing this to be the case. The ways in which Chocky manifests him/herself are resolutely non-physical, and while stretching credibility, are not impossible. People do spontaneously ‘learn to swim’ in extreme circumstances and other people do manage to tap into ways of manufacturing art that produce unsettling or slightly skewed results.

David, the narrator and father of Matthew, is a rational, freethinking man, uncomfortable with ‘common sense’ and questioning of orthodox answers. A self-aware suburbanite, he comments when visited by Mary’s sister and her husband: “Kenneth and I kept mostly to the safe, and only slightly controversial, topic of cars.” The world of the Gore family is comfortable and unremarkable: the world outside of their garden hedge is experienced as being filled with grumpy maths teachers, avuncular policemen, skittish arts teachers and irascible family doctors of English sitcom life.

In the early days of his marriage David decides to move Mary away from her more traditional family, to escape their fecundity, saying of Mary’s family: “There was so many Bosworths that I had a feeling of being engulfed”. Seemingly unable to have children, David wonders at Mary’s need to do so. Rationalising his feelings as despair at the seemingly unending generative powers of the Bosworth family, while revealing an inability for things to be ‘just so’, he tells a friend: “She’s in a circle where it’s kind of a competition in which every married woman is considered ipso facto an entrant – which makes it damned hard on a non-starter.” Ever practical, David and Mary adopt Matthew, and then move the family to Surrey, allowing them to make a fresh start, away from the interfering figures of Mary’s family, soon afterward conceiving Polly.

Both Mary and David, eschewing the traditional, earthy advice of Mary’s sisters, seem insecure in their parenting of Matthew in a way that they don’t of his younger sister, Polly. Throughout the book, Mary and David take it in turns to be dismissive of Polly, telling her to be quiet, or to stop being silly. It is as if they feel comfortable in doing this with a child that they brought into the world themselves, but feel that Matthew is something of an unknown quantity. When Chocky first manifests, Mary says:

“I do wish we knew a little bit more about his parents. That might help. In Polly I can see bits of you and bits of me. It gives one something to go on. But with Matthew there’s no guide at all… there’s nothing to give me any idea what to expect…”

Interestingly, rather than representing a unity, David and Mary are divided in their response to Matthew’s ‘difficultness’. David is more indulgent, at different points instructing Matthew to hide the evidence of Chocky’s presence from his mother. He finds Mary to be too rigid and hard in the face of Matthew’s ‘specialness’. When Matthew informs his parents of Chocky’s departure, completely heartbroken at the loss of this part of himself, David comments after Mary is dismissive of his pain:

Interestingly, rather than representing a unity, David and Mary are divided in their response to Matthew’s ‘difficultness’. David is more indulgent, at different points instructing Matthew to hide the evidence of Chocky’s presence from his mother. He finds Mary to be too rigid and hard in the face of Matthew’s ‘specialness’. When Matthew informs his parents of Chocky’s departure, completely heartbroken at the loss of this part of himself, David comments after Mary is dismissive of his pain:“I have been astonished before, and doubtless will be again, how the kindliest and most sympathetic of women can pettify and downgrade the searing anguishes of childhood.”

Both Mary and David refer to the collusion between David and Matthew in supporting the existence of Chocky. Unable to define exactly what gender Chocky is, Matthew eventually decides that she is more female than male. When David tells Mary this, she answers: “You decide she’s feminine because you feel it will help you and Matthew to gang up on her.”

Throughout the book the reader feels that David, in Matthew’s experiences has glimpsed a land that, maybe, once he himself inhabited. It is as if David, for all of suburban sophistication and outward stability, wishes for something else. Remember that, if this book is taken as being set within a few years of its release, Britain is swinging, the Beatles and the Stones are duking it out in the charts, the world is between the tragedy of Apollo 1, exploding on the dry Florida concrete and the live footage of the planet below beamed back by the triumphant Apollo 7. David seems to want something beyond his nine-to-five family existence. Under the guise of distracting one of Mary’s sisters from expounding her opinions on Matthew, David lets slip his distain for ‘normality’. Talking of his nephew, he says:

“Your Tim is so splendidly normal. It’s hard to imagine him saying anything odd. Though I sometimes think… that it’s a pity that thorough normality is scarcely achievable except at some cost to individuality. Still, there it is, that’s what normality means – average.”

Indeed, it is revealing that when Chocky makes his/her final departure, she takes David aside to explain. With Matthew channelling her voice in a way now familiar from many UFO fringe cults, she outlines her reasons for settling on Matthew and then warns David that Matthew must remain out of sight in life and not attempt to make use of the insights she has provided him into science, as this will lead him into being used badly by the powers that be. She tells David:

“If you are wise you will discourage him from taking up physics – or any science, then there will be nothing to feed their suspicions. He is beginning to learn how to look at things, and to have an idea of drawing, As an artist he would be safe…”

It is almost as if the entire book is a justification for David in allowing his son to follow his own path, harnessing his creativity to find a route out of the constraints of orthodox suburban life of which he is acutely aware. We get a feeling of this from David early on in the book when he mentions the demise of Polly’s imaginary friend Piff, forgotten about on a trip to the seaside:

“I was able to feel quite sorry for the deserted Piff, apparently doomed to wander for ever in summer’s traces upon the forlorn beaches of Sussex.”

It seems to us that Chocky almost represents a way for all of the family to accept that, for Matthew, his path will be the path that leads from suburban dreaming into a more uncertain and more creative future.

Certainly, Chocky does seem a convenient way for Matthew to raise some issues that trouble him. At one point he raises the question of loving two parents at once, and how difficult Chocky thinks this must be, underlining the dichotomy that exists in Mary and David’s relations with him:

“She thinks it must be terribly confusing to have two parents, and not a good idea at all. She says it is natural and easy to love one person, but if your parent is divided into two people it must be pretty difficult for your mind not to be upset by trying not to love one more than the other. She thinks it’s very likely its’ the strain of that which accounts for some of the peculiar things about us.”

Chocky allows Matthew to state very baldly both his dilemma and the dilemma that his parents find themselves in regarding him and his sister. This non physical entity that exists only inside Matthew serves to fulfil a similar role to Grayson Perry’s adventures with Alan Measles, providing a safe way of dealing with anxieties.

Unlike Grayson Perry, who found himself chastised by family for the directions that his fantasy world took him in, Matthew finds acceptance. At the climax of the book, once Chocky has departed, it is David that encourages Matthew to continue his drawing as a way of keeping alive the strange sense of otherness that came to their suburban home.

Rather than changing the entire outside world, the events of Chocky only open up for one child of the surburbs the possibility of exploring further his own interior world. A profound upheaval, if not a world changing one.

In many ways, all of us who fall prey to science fiction or to dreams about the way that the future could be different, do the same thing, escaping when we can into another world inside ourselves, peopled with voices and places that don’t really exist.

Like David Gore, we can’t help but feel that somewhere, there’s always an Alan Measles and a Chocky waiting for the children who left them behind to return.

You can read a slightly abridged version of John Wyndham’s Chocky online here:

http://arthurwendover.com/arthurs/wyndham/chocky10.html

You can buy ‘Grayson Perry: A Portrait of the Artist as A Young Girl’ by Wendy Jones at Amazon.co.uk here

Technorati Tags:science fiction, john wyndham, wyndham, grayson perry, imaginary friends, book reviews, british suburbs

4 Comments:

Another well thought-out and articulate post!

10:06 pm, April 26, 2006

Oh, we do try... Was in serious danger of mangaging to post an article about a book which was longer than the book itself. It's only a slim wee volume you know!

We highly recommend the Grayson Perry book, We were beguiled by it, containing as it does lands ruled by suave teddy bears, insights into the meaning of sheds, how ball bearings are made, the best ways to be a teenage tranny and a quick look at some prime Art Brut.

Smashing stuff or what?

12:23 am, April 27, 2006

Chocky! Oh how I loved this when it was on the telly. Don't think I ever read the book though...

1:37 pm, April 27, 2006

The Grayson Perry book does sound interesting - but, as you know, I'm honour-bound to read some truly dire books in the short term. It's going on my list, though.

2:58 pm, April 28, 2006

Post a Comment

<< Home