Meme Therapy: Archeology of the Future guest blogs on SF Memes

Meme Therapy: Archeology of the Future guest blogs on SF Memes

Meme Therapy: Archeology of the Future guest blogs on SF Memes

In response to a discussion at Meme Therapy, Archeology of the Future has managed to escape from the twisted wreckage of Winnerden Flats for long enough to discuss Science Fiction memes. Responding to a previous discussion, Archeology of the Future advances the idea that rather than Science Fiction ideas being more prevalent now in popular culture than in the past , it is that Science Fiction fandom is more watchful and ready to cry foul when the wolf of popular culture snatches an idea from the cosy enclosure labelled SciFi.

Science Fiction is, in its most potent form, only a distorted mirror of the present. Science Fiction ideas are tools and machines for making new and surprising understanding...

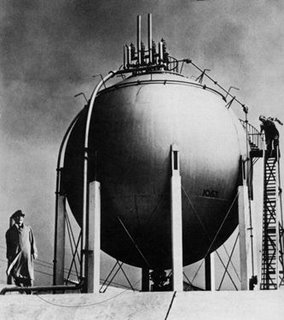

The postcard that accompanies this post can be considered a trailer for an excavation that we're currently undertaking at the request of a regular reader. Just taking in what's going on in the photograph should give you an idea of what's in store when we present what we've dug up...

Thanks to Meme Therapy.