Science Fiction and the Suburbs

Science Fiction and the Suburbs

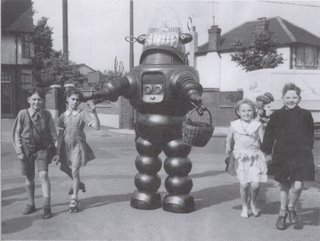

Sometimes you come across something that speaks to something inside of you that you didn't even know was there. In many ways the origin of this blog can be traced back to a single photograph. You can see it here. The photograph is labelled "In July 1956 Robby visited New Malden as part of a trip to promote Forbidden Planet". It appears in 'SF:UK' by Daniel O'Brien. It is one of Archeology of the Future's favourite pictures ever.

Sometimes you come across something that speaks to something inside of you that you didn't even know was there. In many ways the origin of this blog can be traced back to a single photograph. You can see it here. The photograph is labelled "In July 1956 Robby visited New Malden as part of a trip to promote Forbidden Planet". It appears in 'SF:UK' by Daniel O'Brien. It is one of Archeology of the Future's favourite pictures ever.There are so many beautiful and suggestive details in it as an image that it seems to sum up something about Science Fiction and Britain that it is like a map of territory barely explored, beguiling and filled with promises of riches available to the brave adventurer should they chose to begin the journey.

The suburbs of the thirties and forties built semis are spooky places to begin with, as they represent a dream of life embodied in plasterwork and hedges and windows inset with coloured stained glass. The suburbs are quietness, control, a sunny land between city and country. They are a place where humanity is atomised and separated. The patterns of streets and houses minimise the uncomfortable sense of unpredictability that the overlapping of lives and people in The City brings. Meetings and interactions must be planned. For some this is comfort and stability, for others this constitutes an eternal stasis, waiting and longing for something, anything to happen.

Once you have walked down your driveway and closed your door, you are allowed to be anything you can dream of being. In bedrooms and garden sheds, people create whole fantasy lives for themselves. They begin the process of becoming something else, something that transforms them. In the city, everything is about interaction, whether chosen or not. Other people are unavoidable. You can become anonymous or peacock-like in the city, but you always do it in the company of The Crowd. Due to the density of people, of industry, of work and shopping and all of the other actions of human existence, the City is unpredictable. It moves and shifts on its own, far greater than the sum of individuals in it. Whatever happens happens in public in one form or another.

In the suburbs, as long as it doesn’t happen in public, anything goes. As long as your actions don’t impinge on someone else’s space, they are fine, unknown maybe but fine. You can be as radical, as regressive, as whimsical, and as normal as you wish, as long as you’re behind your own front door. The suburbs produce the eccentrics and the enthusiasts of which Britain is so celebratory.

The suburbs in Britain are like a great dream battery, a place where energies and longings collect, waiting to be put to some sort of use. People want something else, but in their houses on their own, they can never tell if anyone else wants the same.

Imagine the suburb of New Malden in 1956. The Suez crisis is in full swing. England the great is becoming tarnished, the World is minutes away from Sputnik and a sense that the heavens are far closer than they have ever been before. The Rock ‘n’ Roll years have barely begun…

Look at the children in the photograph, dressed as children might have been a decade ago. They’re quite possibly the fruit of returning soldiers, born into the optimism of the post-war period. They’re standing in that street in the gap between Quatermass 2 and Quatermass and The Pit. Everything seems calm and ordered…

And there he is, Robbie the Robot, looking bewildered, an exotic growth transplanted. How did he find his way there? Despite being a piece of high American design, he somehow looks at home; as if by sheer force of will the dreamers of the suburbs have created him there and then. Modernist design does poke its way into suburbs in the strangest places. It crops up in public buildings mostly, and the odd secluded street. There are Sci-fi curves and moulded concrete painted blinding white vying for space with Tudor fronting and muted classic flourishes. Every so often, it seems that a dream has managed to push through to make itself real.

So it is with Robbie, lost and befriended by children already alive to the possibilities of technology. Looking at their faces, they look like they have always fully expected that a robot will turn up in their street, or that something else equally exciting will occur in payment for all of the years they have waited for something exciting to happen. Robbie is a visitor in many ways adrift in a land very different from the one in which he originated. He has arrived from a land of colour, a land of noise and movement and, basket in hand, is trying to acclimatize himself to this strange world of things that are both new and old at the same time, steeped in tradition yet also freshly minted.

We defy you to look at this picture and not feel a strange and elusive magic, a sense of something difficult to define about Science Fiction and childhood and England captured and expressed.

In quiet streets, fantastic things happen…

The juxtaposition of the ordinary and the extraordinary is a fundamental of UK Science Fiction.

Buy SF:UK: How British Science Fiction Changed The World at amazon.co.uk

Technorati Tags: science fiction forbidden planet suburbs