As promised, Archeology of the Future has returned to share the remainder of our bank holiday activities with you...The Traveller On Returning

As promised, Archeology of the Future has returned to share the remainder of our bank holiday activities with you...The Traveller On Returning

Saturday was, of course, the return of a champion, reborn and made anew for each generation. David Tennant, as the latest incarnation of Doctor Who in the popular BBC Television children’s programme of the same name is, on this showing and his first appearance on Christmas day last year, a more disturbing proposition than any of his previous incarnations.

Saturday’s programme, in which The Doctor and Rose, his South east London travelling companion, visit the home of humanity in the far distant future and uncover a conspiracy in its eqivilent of the National Health Service, revealed a Doctor who was by turns beguiling and unsettling. For the first time since childhood, we found ourselves wildly jealous of the Doctor’s assistant, ready to throw all caution to the wind and join the Doctor in whatever adventure he chose.

This Doctor has the wild eyes and quicksilver emotions of a manic-depressive, one moment goggle eyed with childish wonder, the next cynical or flip, suddenly moving to righteous anger and then wet eyed emotion. He is also more self consciously dandy-ish, coming across as more mannered, more brittle than his predecessor. Whether through accident or design, this Doctor is far less centred than Chris Ecclestone’s portrayal of his previous regeneration. Despite his energy and his zaniness, Ecclestone’s Doctor exuded solidity and strength, and a quiet kind of reassurance. Tennant’s Doctor is, on these early showings closer to a Harlequin. Witness this description of Harlequin from wikipedia:

“His everlasting high-spirits and cleverness work to save him from several difficult situations his amoral behaviour gets him into during the course of the play. In some Italian forms of the harlequinade, the harlequin is able to perform magic feats. He never holds a grudge or seeks revenge.”

The reason this connection occurs lies in our reading of ‘A Cure fore Cancer’ by Micheal Moorcock as detailed in this previous post. Jerry Cornelius is specifically refered to as a Harlequin, an essentially immoral and clever dandy figure whose appetites get him into trouble. Everything is farce to him and nothing important, making him immoral in the way that a child is. It is the strutting, peacock nature of him and the way in which the tone of him alters dependant on the mood of his times that puts us in mind of the current Doctor. His enthusiasm to explore and adventure is the only thing that precipitated the events of Saturday’s episode. For all of his cleverness, charm and charisma, he was essentially dancing between events he set in motion but could not control.

Watching, Archeology of the Future couldn’t work out whether we wanted to follow him or, more worryingly, be him or be like him. Imagine that, being able to escape into time and the wide universe at will, to skip where and when you pleased…

The Most Science Fiction Place In London

The Most Science Fiction Place In London

On Sunday, Archeology of the Future found ourselves in the most Science Fiction place in London. Standing in the wet artificial heat, surrounded by the sound of birdsong and the fecundity of huge tropical plants climbing and possessing grey concrete walkways, eyes drawn astray by the golden flash of fish in cool water, we thanked whatever powers that exist that the relentless marches of time have overlooked the Barbican Conservatory.

For those of you unfamiliar with The Barbican, it is a huge housing development that brings together flats and houses, amenities, gardens, a huge theatre, cinemas, offices and green spaces in the City of London. Designed originally as social housing, it is the most well realised example of utopian architectural practice in the UK. Everything about it screams out possibilities of new ways of living, new ways of constructing life in a city. It was purposely built so that everyone could feel themselves to be an actor in a great drama of their own. Through a long gestation period, where different pieces of the development were design, modified, scrapped, reinstated and then finally built, The Barbican absorbed all of the new ideas and experimental developments of British architecture, making it like a dream of possible future architectures. It is here that Archeology of the Future has a spiritual home and here that we shall explore in far greater depth in future posts.

The Conservatory, opened in 1984, was a late addition to plans and is like a set for a botanical area onboard a space station. Walkways criss-cross the high vault under the glass exterior. Even the interior doors have rounded corners suggestive of airlocks. There is just something so incongruous, so wondrous about the sheer artificiality of the space, surrounded by tall concrete towers and brown brickwork, looking out beyond to the ever growing office towers of Moorgate. Standing there, Archeology of the Future could see the possible future, the new people meeting there under their artificial canopy, the last generation to have a faith in the possibility of changing the course of the future.

Archeology of the Future wasn’t even aware of the existence of The Conservatory until an afternoon exploring amongst the different levels and structures delivered it to us as we rounded a corner. It was like a homecoming. All of the beautiful dreams of bringing nature and artifice together in way that it can be enjoyed at the leisure of the participant come together for us under the glass. The nearest that we can think of is the kind of thing that you get in some large corporate buildings or shopping developments, but this so radically different that the similarity is only fleeting. The Barbican Conservatory is no less than a stab at an artificial Eden, a place to play without being directed or moved on…

Archeology of the Future wasn’t even aware of the existence of The Conservatory until an afternoon exploring amongst the different levels and structures delivered it to us as we rounded a corner. It was like a homecoming. All of the beautiful dreams of bringing nature and artifice together in way that it can be enjoyed at the leisure of the participant come together for us under the glass. The nearest that we can think of is the kind of thing that you get in some large corporate buildings or shopping developments, but this so radically different that the similarity is only fleeting. The Barbican Conservatory is no less than a stab at an artificial Eden, a place to play without being directed or moved on…

The Conservatory is being run with a skeleton staff now, and is ever having its opening times reduced. Only open on Sundays now, the popular consensus is that it is being run into the ground before it is closed. This enhances the charm, because there is a sense of the working future, where people patch thing up and things evolve rather than being pristine.

If you have the opportunity, we advise you to visit this beautiful glass bubble outside of time while you can. If Archeology of the Future were ever to meet any of you, our audience, it would be among the green fronds of the Conservatory

Designing a New World

Designing a New World

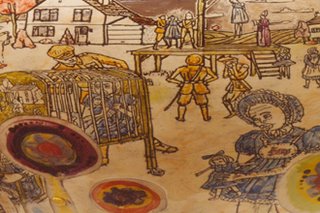

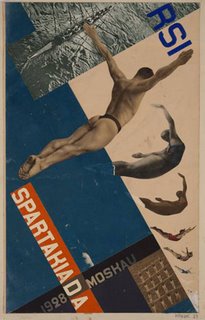

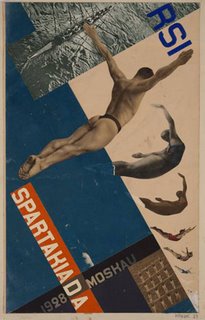

On Monday, Archeology of the Future made it to the wide, spy haunted streets of South Kensington to visit the Victoria & Albert Museum to see the Modernism 1914-1939: Designing a New World exhibition. It was an exhibition that we’d been waiting for since our teens, bringing together as it does the largest collection of modernist objects ever in one exhibition in the UK. The effect was like sherbet fizzing in our brains, or more correctly, finding that other people shared the dreams you’d nursed inside of you since childhood too.

Exhausted by the First World War and energised in one way or another by the Russian Revolution, a generation of artists and designers worked to literally remake the world and bring about a future where the division between art and everyday life was dissolved and where the terrible weight of the past could be escaped. At this exhibition, everything in one-way or another, was Science Fiction.

We point this out, because as we said in a previous post, Archeology of the Future is about Science Fiction as a practice of looking or a way of interrogating the world. Too often Science Fiction is limited and inward looking, happy to exist on its own as a genre. In an essay on Philip K. Dick, the late Stanislaw Lem recognised this. Comparing genre fiction to a situation where natural selection is frustrated or interrupted he states:

“In culture an analogous situation leads to the emergence of enclaves shut up in ghettos, where intellectual production likewise stagnates because of inbreeding in the form of incessant repetition of the selfsame patterns and techniques. The internal dynamics of the ghetto may appear intense, but with the passage of years it becomes evident that this is only a semblance of motion, since it leads nowhere, since it feeds into nor is fed by the open domain of culture, since it does not generate new patterns or trends, and since, finally, it nurses the falsest of notions about itself, for lack of any honest evaluation of its activities from outside.”

Walking around the Modernism exhibition, it was clear to us that for the men and women involved in creating the artefacts on show, the division between Science Fiction and the real world would have seemed laughable, as they were actively engaged in a process of trying to build a new future. Everything was geared toward making the future happen in the present, to changing and making anew.

We advise anyone with even a passing interest in the idea that it possible to find new ways of organising or living human existence to get along there. It’s on until 23 June 2006, and worth travelling for.

It was too much for us to take in, so we bought a badge that says ‘UTOPIA’ from the shop on our way out of the exhibition and began plotting ways to skive off work and visit again.

For Archeology of the Future, it was like finding a home.

For more information on Modernism 1914-1939 visit the V&A minisite here.

The essay 'Philip K. Dick: A Visionary Among Charlatans' by Stanislaw Lem appears in the anthology 'Microworlds'. Buy it from amazon.co.uk here. Doctor Who is broadcast on Saturday nights in the UK, as it should be. It is best watched whilst eating beans on toast.More excellent photographs of the Barbican can be found here, here and also here. The conservatory photograph was taken by sleekit, the waterfall by will survive.

Doctor Who is broadcast on Saturday nights in the UK, as it should be. It is best watched whilst eating beans on toast.More excellent photographs of the Barbican can be found here, here and also here. The conservatory photograph was taken by sleekit, the waterfall by will survive.

Technorati Tags: science Fiction, doctor who, barbican, modernism

Barbican Conservatory: A virtual garden?

Barbican Conservatory: A virtual garden?